How big could the cloud get?

If you’ve read my other posts you know that I like to explain things through analogies. The cloud is on its way to becoming as core to life as electricity. My goal with this post is to explain why that statement isn’t an exaggeration. Below I will:

Compare the cloud to the proliferation of electricity and the grid

Explain why the “base-layer” of the cloud makes it unique among transformational technologies from the perspective of investors

Walk through how ubiquitous the cloud already is today

Use Netflix as a case-study to help us more granularly understand the cloud’s benefits

Finish with a teaser for my next post which will begin diving into examples of use cases the cloud will enable in the future - which will keep the demand for cloud resources growing exponentially for a long time to come

The proliferation of electricity

Thomas Edison patented his lightbulb in 1879. John Pierpont Morgan was one of his first customers (and an investor), and had Edison install an on-site generator to power hundreds of lightbulbs in his Manhattan mansion.

In 1882 Edison’s Pearl Street Station opened in lower Manhattan. It was the first central power station in the US, but it was based on direct current, which limited its range to half a mile. In 1896 George Westinghouse used alternating current - what our electric grid runs on today - to connect Niagara Falls to Buffalo 20 miles away.

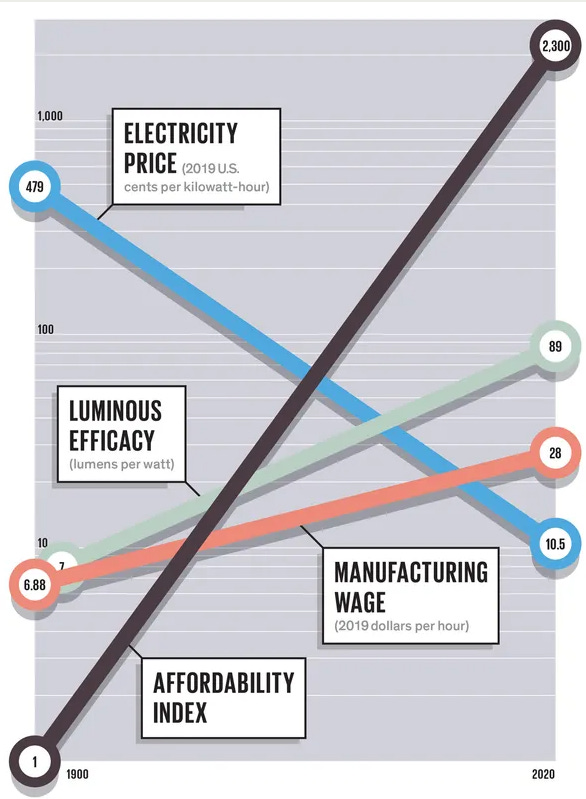

Electricity’s first use cases were around enabling the replacement of an inferior good with something better. Candles (inferior good) were replaced by lightbulbs. On-site steam-powered generators were replaced with a connection to an electric-power station. As electricity proliferated the cost to produce and distribute it plummeted. The following comes from a blogpost on IEEE.org:

When expressed in constant 2019 dollars, the average price of electricity in the US fell from $4.79 per kilowatt-hour in 1902 (the first year for which the national mean is available) to 32 cents in 1950. The price had dropped to 10 cents by 2000, and in late 2019 it was just marginally higher, at about 11 cents per kilowatt-hour. This represents a relative decline of more than 97%. A dollar now buys nearly 44 times as much electricity as it did in 1902.

Because average inflation-adjusted manufacturing wages have quadrupled since 1902, blue-collar households now find electricity about 175 times as affordable as it was nearly 120 years ago.…And it gets better: We buy electricity in order to convert it into light, kinetic energy, or heat, and the improved efficiency of such conversions have made the end uses of electricity an even greater bargain.

Lighting offers the most impressive gain: In 1902, a lightbulb with a tantalum filament produced 7 lumens per watt; in 2019 a dimmable LED light delivered 89 lm/W. That means a lumen of electric light is now three orders of magnitude (approximately 2,220 times) more affordable for a working-class household than it was in the early 20th century. Lower but still impressive reductions in end-use costs apply in the case of electric motors that run kitchen appliances and force hot air into the ducts to heat houses using natural-gas furnaces.

It took 46 years for 50% of all houses in the US to get electricity, twenty more to hit 75%, and 11 more to reach 100%.

Imagine Jane Doe walking down Broadway in the early 1900s, marveling at the ubiquitous lights. What might she have said in response to the question: “What does an electric future look like?”

Jane might have predicted that electric lights would spread to cities around the world, even cities in poorer countries. It was newsworthy whenever a big business, hotel or factory made the switch to electric, so Jane probably would have guessed that most large organizations would end up connecting to the grid. She might even have posited that lightbulbs would eventually find their way into people’s homes…

While replacing dangerous flammable candles with lightbulbs and building an electric grid capable of powering businesses would have been transformational in itself, the bigger changes brought by electricity would have been inconceivable at the time.

Cheap electricity turned swampy, mosquito-laden Florida into the hottest (pun intended) destination in the country. It catalyzed the great migration south and opened up tens of millions of acres in Florida alone to people that never would have moved without affordable indoor cooling.

Cheap electricity facilitated the proliferation of home-appliances. Dishwashers, washing machines and other appliances would save the average household 40 hours per week. These newly available hours enabled women to enter the workforce en masse.

Cheap electricity gave architects access to the skies. Without electric elevators and lighting, the Starrett Corporation never would have built the Empire State Building.

To summarize:

A steam-powered on-site generator is equivalent to on-premise IT infrastructure

The cloud is the electric grid itself, with each data center being the equivalent of a power station

Lightbulb efficiency being improved in terms of lumens emitted per watt of electricity is analogous to the creation of service offerings built on the cloud that make migrating and using it far easier and more rewarding per dollar spent

Florida; home-appliances enabling women to enter the workforce; skyscrapers- represent the magnificent and unpredictable knock-on effects that the cloud will bring in the future (see healthcare teaser at the end)

I want to make one final point before moving on to the base-layer. I believe electricity delivers the best analogy to the cloud, but as an innovation, it is not unique in causing magnificent and unpredictable knock-on effects.

Modern humans - homo sapiens - spent around 300,000 years as hunter gatherers. Then farming came along 12,000 years ago, and it took only a few millennia for it to become the dominant source of food. Farming lead to hierarchical societies and the concentration of resources. Concentrated resources enabled specialization. Specialization created a need for markets and trade, which in turn necessitated the invention of money.

The internet and computers created new types of network effects that spawned the era of tech giants. The five largest tech companies in the US (Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Tesla and Meta) are now worth more than the entirety of publicly traded companies in Europe.

Nearly half of people spend 5 hours a day on their smartphone, and another 20% spend more than three. Smartphones:

Brought internet access to billions of people who couldn’t afford computers

Brought hundreds of millions of people into the world of banking

Caused the price of wireless technologies and sensors to plummet, making things like continuous glucose monitors possible (no more finger-pricks for diabetics)

Doubled the size of the gaming market virtually overnight

THE CLOUD will undoubtedly take its place in the Pantheon of transformational innovations, but from the perspective of investors the cloud is unique among the aforementioned technologies due to what I call the base-layer.

The base-layer is my term for the businesses that own the data centers and hardware: Amazon’s AWS, Microsoft’s Azure, and Google’s GCP. Economies of scale, network effects and lock-in mean that it is unlikely another entrant will obtain meaningful market share (possible runners for 4th place include Oracle and Alibaba - but neither has a chance of reaching 3rd place). This means that the market will remain an oligopoly with oligopoly margins. Knowing so early in a new technology’s proliferation-lifecycle who the biggest winners are going to be, especially given the valuations they’re trading at - is unique to the cloud.

There’s another important distinction to make between the cloud and electricity. The supply side centralization of electricity as a utility is not even close to that of cloud computing. On top of that, the base-layer businesses - unlike the electric utilities - are not relegated to just providing stale access to databases and compute power. The base-layer companies:

Are constantly improving data-center architecture, working with companies like Nvidia and AMD to design new application-specific chips, eking out more performance from their GPUs and networking gear and increasing energy efficiency. There is no end in sight to the potential for architectural improvements…

Have enormous opportunities (which they are already executing on) to add new service offerings that range from the basic (packet routing) to the cutting edge (machine learning and artificial intelligence) - which they can upsell to their customers

Have a lock on supply of the cutting-edge logic semiconductors on which everything relies - and which will remain supply constrained for years to come

Are better positioned than anyone to be the providers of “home appliances” and “LED Lightbulbs”…

One final point before moving on to the cloud’s current ubiquity: the potential total addressable market (TAM) of the base-layer is far larger than any TAM in history within an oligopolistic market - and it may end up being the largest TAM period…

There is an obvious takeaway here for investors. Buying the base-layer is an obvious and relatively low-risk way to invest in the cloud’s proliferation.

The cloud is already ubiquitous

AWS stands atop the Big 3. It grew revenues 40% YoY, a truly stunning figure considering the business has run-rate revenues of $71 billion annually, and operating margins around 30%.

Time for another anecdote, borrowed from my deep dive on semiconductors. Consider the case of a business that sells products online. They must:

Have a website built on a platform like Shopify or Wordpress

Maintain a library of product photos and videos (could be done in iCloud)

Subscribe to various software-as-a-service (SaaS) products, like:

Salesforce (customer relationships)

Twilio (online chat-apps like the ones you see pop up on web-pages asking if you have any questions)

Intuit (accounting software)

Fulfilled by Amazon (inventory tracking and shipping)

Zoom (virtual meetings)

Adobe (graphic designs)

Stripe (collect payments)

Every one of those services is cloud-based. iCloud is built on GCP and AWS. Salesforce, Twilio, Intuit, Zoom and Stripe are all AWS customers. Adobe uses both AWS and Azure. Shopify resides on GCP, and Wordpress can be used with any of the aforementioned Big 3.

But it’s not just technology and SaaS companies anymore…Virtually all businesses are in process of moving more of their IT spend to the cloud.

Walmart: “Has deployed Microsoft’s cloud technologies, including AI and machine learning, across a range of functions, including purchasing algorithms, and sales data sharing and management.”

Procter and Gamble: “Once we implemented Ultra Disk Storage, we had our eureka moment. We knew our initial move to the cloud would be challenging; however, it was less daunting once we saw the throughput those disks could give us.”

BMW: “As part of the wide-ranging collaboration, the BMW Group will migrate data from across its business units and operations in over a hundred countries to AWS. The move will encompass a number of the BMW Group’s core IT systems and databases for functions such as sales, manufacturing, and maintenance.”

Starbucks: “Customers receive tailor-made order suggestions generated via a reinforcement learning platform that is built and hosted in Azure. Through this technology and the work of Starbucks data scientists, 16 million active Starbucks Rewards members now receive thoughtful recommendations from the app for food and drinks based on local store inventory, popular selections, weather, time of day, community preferences and previous orders.

If you google the name of any business + “cloud provider” something will pop up. Here’s a two year old list of some AWS customers with name-recognition:

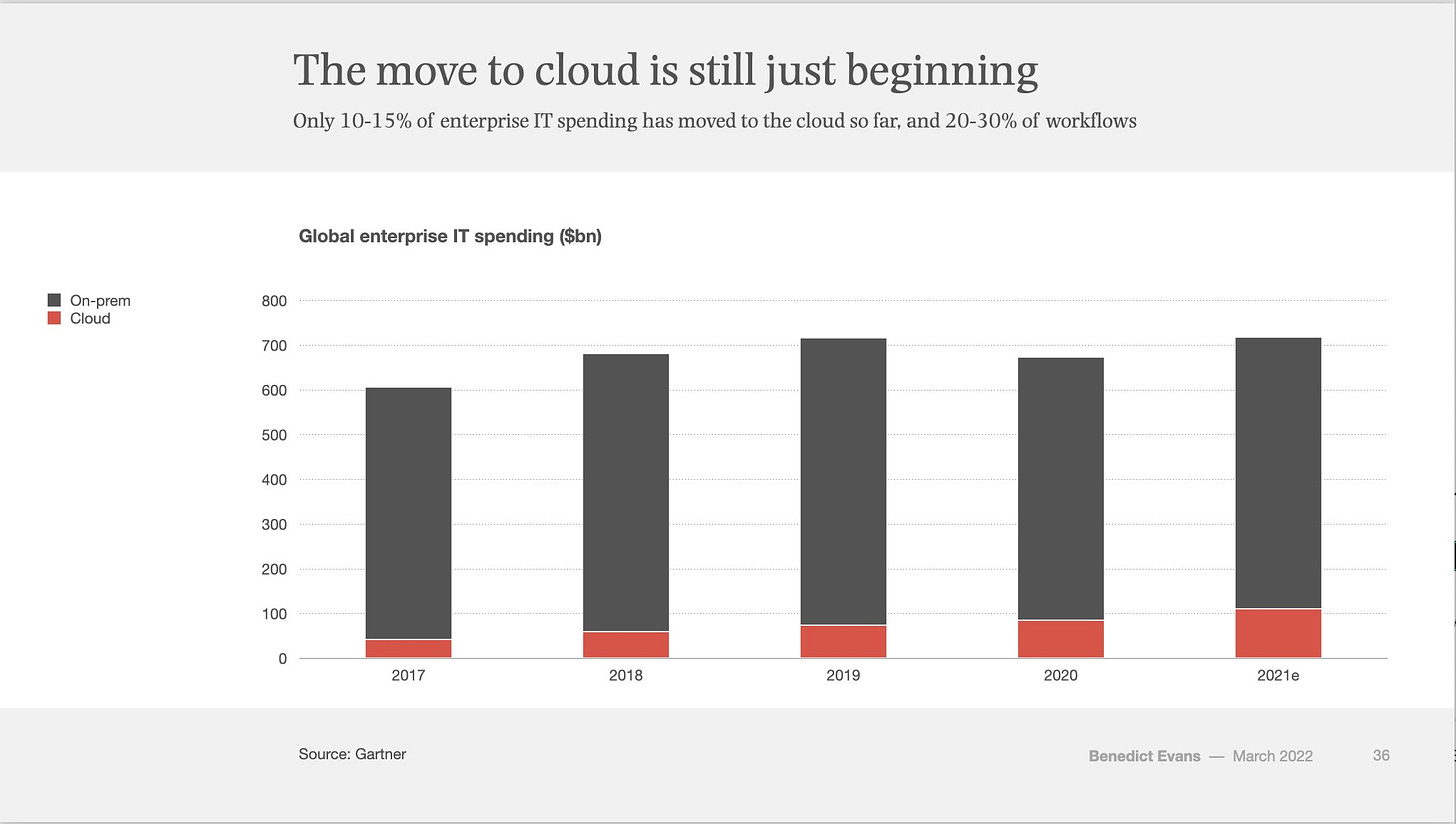

Yet… for all the talk about the high-growth cloud-first SaaS businesses, it is the migration of legacy IT infrastructure that accounts for most of cloud growth today - and it’s still just getting started.

The estimate above ended up being low for 2021.

One last interesting snippet that came from an interview I did with a senior e-commerce developer. He pointed out that if any business relies heavily on Google Analytics then they will end up being a GCP customer (they might use other clouds as well, but they will certainly also use GCP). Given that Google Analytics is by far the most ubiquitous web analytics tool on the internet, this provides a very powerful funnel to drive GCP growth (and keep those customers locked-in).

The question begs, what’s so great about the cloud?

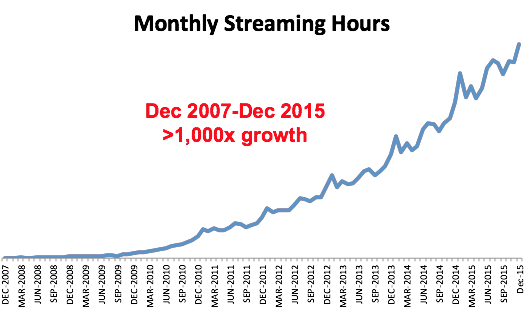

Netflix is an ideal case study to elucidate the cloud’s benefits. They were prescient in realizing that running their own data centers (on-premise) was not viable given their rate of growth, and began migrating to AWS in 2008. The following excerpts come from a blog post written in 2016 by Yuri Izrailevsky, Vice President of Cloud Computing and Platform Engineering for Netflix, where he talks about Netflix’ migration to AWS on the eve of its completion…7 years after they started.

Our journey to the cloud at Netflix began in August of 2008, when we experienced a major database corruption and for three days could not ship DVDs to our members. That is when we realized that we had to move away from vertically scaled single points of failure, like relational databases in our datacenter, towards highly reliable, horizontally scalable, distributed systems in the cloud. We chose Amazon Web Services (AWS) as our cloud provider because it provided us with the greatest scale and the broadest set of services and features…

The Netflix product itself has continued to evolve rapidly, incorporating many new resource-hungry features and relying on ever-growing volumes of data. Supporting such rapid growth would have been extremely difficult out of our own data centers; we simply could not have racked the servers fast enough. Elasticity of the cloud allows us to add thousands of virtual servers and petabytes of storage within minutes, making such an expansion possible. On January 6, 2016, Netflix expanded its service to over 130 new countries, becoming a truly global Internet TV network. Leveraging multiple AWS cloud regions, spread all over the world, enables us to dynamically shift around and expand our global infrastructure capacity, creating a better and more enjoyable streaming experience for Netflix members wherever they are.

Instead of needing to build data centers all over the world based on a “best-guess” as to how much demand would come from each of the new geographies, Netflix could add capacity in whatever geography was needed by doing little more than clicking buttons. AWS handled the rest. This means Netflix avoided:

Finding space to lease or purchase

Building out the physical shells

Buying and installing hardware and software

Hiring and training employees

And they avoided that headache multiplied by the number of locations they would have needed to build to adequately cover 130 new countries… This saved Netflix literally billions of dollars of capex.

The cloud allowed us to significantly increase our service availability. There was a number of outages in our data centers, and while we have hit some inevitable rough patches in the cloud, especially in the earlier days of cloud migration, we saw a steady increase in our overall availability, nearing our desired goal of four-nines of service uptime (99.9999%). Failures are unavoidable in any large scale distributed system, including a cloud-based one. However, the cloud allows one to build highly reliable services out of fundamentally unreliable but redundant components.

A key feature of the cloud is built-in redundancy. If you want redundancy in a system that you are building for yourself (on-premise) then you need to have extra servers, extra capacity, extra networking-equipment, extra everything so that when something goes down you can switch to the backup. All of that “extra” means more capital investment. Worse still, in some places you won’t end up needing the redundancy, in which case the money will have been wasted.

Cost reduction was not the main reason we decided to move to the cloud. However, our cloud costs per streaming start ended up being a fraction of those in the data center – a welcome side benefit. This is possible due to the elasticity of the cloud, enabling us to continuously optimize instance type mix and to grow and shrink our footprint near-instantaneously without the need to maintain large capacity buffers. We can also benefit from the economies of scale that are only possible in a large cloud ecosystem.

If you are running on-premise then you need to have enough hardware installed to handle peak demand – In Netflix’s case this is a figure which is changing constantly based on geography, time of year, and content release schedule. Essentially, if their maximum streaming use occurred from 6-11PM EST during summer break, and required enough bandwidth to stream to 100 million households simultaneously – then they needed to purchase enough hardware to stream to 100 million households concurrently (plus more hardware if they want redundancy). At 4am on a Tuesday in October the machines are still there, sitting idle, being wasted…

Given the obvious benefits of the cloud, why did it take us a full seven years to complete the migration? The truth is, moving to the cloud was a lot of hard work, and we had to make a number of difficult choices along the way. Arguably, the easiest way to move to the cloud is to forklift all of the systems, unchanged, out of the data center and drop them in AWS. But in doing so, you end up moving all the problems and limitations of the data center along with it. Instead, we chose the cloud-native approach, rebuilding virtually all of our technology and fundamentally changing the way we operate the company. Architecturally, we migrated from a monolithic app to hundreds of micro-services, and denormalized our data model, using NoSQL databases. Budget approvals, centralized release coordination and multi-week hardware provisioning cycles made way to continuous delivery, engineering teams making independent decisions using self service tools in a loosely coupled DevOps environment, helping accelerate innovation. Many new systems had to be built, and new skills learned. It took time and effort to transform Netflix into a cloud-native company, but it put us in a much better position to continue to grow and become a global TV network.

During my research for this post I ran across a few different “migration guides” that said some variation of the following (they were speaking to large organizations): Don’t migrate to the cloud if the only benefit you are expecting is to cut costs.

I’ve also started running across people making the case that if your business is stable and predictable, it may end up being more cost effective to stay on-prem. The logic here is that because of the lock-in it’s not really feasible to move off the cloud once you are on it. So, companies on the cloud are going to end up paying fees to the base-layer from now until Judgment Day. These fees will outweigh the benefits of elasticity and flexibility for more mature companies.

My research tells me that this is incorrect. Anecdotally, I also interviewed a senior AWS engineer at an F500 company for this piece. He told me that their business did expect to save money by moving to the cloud, but they were equally attracted by the flexibility, security, elasticity and redundancy. All that being said, they ended up saving costs an order of magnitude greater than what they had modeled out.

Netflix is a company famous for its technological prowess. They hire senior developers whenever possible and pay them through the nose. Even though it took Netflix a long time - and even though they had to build many systems from scratch - they still think the cloud is the greatest thing since sliced bread. And, they thought that even when migrating was an order of magnitude harder than it is now. It is easier to migrate than it ever has been and getting easier all the time. And, once you’re there, you have a multitude of service offerings waiting for you - service offerings Netflix was having to build for itself. The moat is growing…

I’m going to wrap up with a teaser on how cloud-intensive healthcare might become in the future…

Scanning a human genome requires about 200 gigabytes of data. Right now, the benefits of knowing a genome are pretty limited, but that will change in the future. Eventually it will become a standard of care for every person to have their genome sequenced. On top of the 200 gigabytes of raw data are another 100 gigabytes of data that get generated by the analysis. 300 gigabytes of data X 8 billion people is 2.4 zettabytes. For reference, there was about 44 zettabytes of data on Earth as of the beginning of 2020. But scanning a genome is a one time thing…

The following excerpt comes from Chronomics:

Your genes and DNA don’t change; but how they are expressed does. What determines the how is epigenetics.

Genetic testing tells you disease risk which you cannot change. It ignores lifestyle and environmental factors and is therefore limited in measuring your risk of illness such as heart disease, diabetes, dementia and cancer.

Epigenetic testing, on the other hand, brings your DNA to life, combining your risk of long-term illness with actionable lifestyle and environmental factors you can change.

MedlinePlus puts it like this: Epigenetic changes are modifications to DNA that regulate whether genes are turned on or off. These modifications are attached to DNA and do not change the sequence of DNA building blocks.

I’ll finish with this snippet from David Sinclair’s (Harvard geneticist) excellent book: Lifespan: Why We Age - and Why We Don’t Have To:

Increasingly, DNA can also tell you what foods to eat, what microbiomes to cultivate in your gut and on your skin, and what therapies will work best to ensure that you reach your maximum potential lifespan. And it can give you guidance for how to treat your body as the unique machine that it is.

Just imagine the amount of data that will be created and processed when your annual physical involves getting an epigenetic test, not to mention the health nuts that will get a test done every few months.